The 13 cases submitted in the past week to the city Department of Consumer and Worker Protection fall under a new law requiring weekly payments. Workers say they’ve been unfairly locked out of their accounts.

Claudia Irizarry Aponte, The City

This article was originally published on Aug 2 5:00am EDT by THE CITY

It was a routine user identification procedure Simitrio Felix had followed before.

Every year, DoorDash asks workers to resubmit their tax identification number, emails, phone numbers and other documents for tax purposes and to confirm the identity of the owner of the account. Felix, who’d been working as a delivery “Dasher” for about a year and a half, submitted all of the information to the company, including his tax identification number, known as an ITIN.

The company, he said, never sent him a follow-up verification email, which he described as the final step in completing the process. Then it locked him out of his DoorDash account — and withheld a $1,200 paycheck he said he’d earned that week.

“It makes me very angry,” said Felix, who spoke to THE CITY in his native Spanish. “This is my only job, and when I lost access to my account I had nothing else to fall back on. I submit all my paperwork, follow all the company and the customer’s instructions, and to lose my account and money in the process is very frustrating.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24824101/080123_doordash_suit_3.jpg)

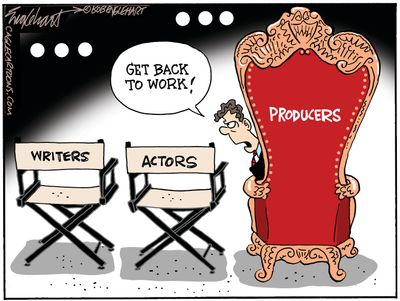

Deliverista Rosendo Tacam shows a message on his phone showing he lost access to his DoorDash account in April after receiving a negative customer review. | Claudia Irizarry Aponte/THE CITY

Felix is one of 13 DoorDash delivery workers who filed complaints against the company between July 26 and Tuesday alleging wage theft, cases now being investigated by the city Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP). The investigation falls under a 2022 local law that guarantees app-based food delivery companies pay workers weekly.

The Workers Justice Project, the parent organization of delivery worker advocacy group Los Deliveristas Unidos, helped Felix and the other 12 workers file their complaints.

The 13 complaints cover alleged missed pay mostly between April and May of this year, and collectively amount to nearly $22,000 in lost wages, according to WJP. Meanwhile, the group is fielding more than 50 additional complaints totaling an additional $55,500, all of them regarding wage theft allegations against DoorDash.

Department spokesperson Michael Lanza confirmed DCWP is investigating wage theft complaints regarding DoorDash and urged “any delivery worker who believes they have not been paid” to reach out to the agency.

“DCWP has received complaints from delivery workers alleging DoorDash did not pay them for work they performed, and we are investigating,” Lanza said in a statement. “The investigation covers these complainants and any other DoorDash workers who may have experienced late payment or nonpayment.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24022731/091422_doordash_1.jpg)

A deliverista works for DoorDash in Midtown, Sept. 14, 2022. | Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

In a statement, DoorDash spokesperson Eli Scheinholtz said the company “strongly reject[s] these false and baseless allegations,” which he described as being pushed by “thinly-veiled political motivations.”

“We can confirm that some of these Dashers were deactivated for providing false information and others were unable to confirm their necessary financial details,” Scheinholtz wrote in an email statement, referring to the cases of five workers who submitted complaints to DCWP and spoke with THE CITY. “We have fair and clear standards that we hold all Dashers to, and we will always give anyone an opportunity to appeal if there is an issue with their account.”

“We look forward to engaging with the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection to correct the record and clear up this misinformation,” he added.

Locked Out

Many delivery workers toiling in the gig economy who lose access to their accounts, or don’t have proper tax identification in the first place, find creative — and risky — ways to work anyway.

Many undocumented delivery workers sign up for the apps under assumed identities, or submit fake IDs, and work until they get caught.

Others share accounts with friends and family, and others rent accounts, paying the owner either a percentage of their weekly delivery earnings or as much as $500 a month.

Companies typically flag suspicious accounts when it realizes it appears to be active throughout the whole day — a sign that multiple people share the same account — or when a customer submits a complaint alleging that the person who delivered their meal is not the same person pictured on their screen, workers say.

At DoorDash, a customer complaint about a worker’s identity doesn’t immediately trigger a deactivation, but it does generally result in a search for other inauthentic behavior tied to the worker’s account. Removing a worker from their platform, the company says, is a final resort.

In New York City, all app-based food delivery companies are required to pay workers at least once a week under a law that has been in place since 2022. That law was inspired by THE CITY’s reporting on delivery workers’ struggles on the job, including what workers say are wage theft and withheld tips.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24016535/091222_doordash_1.jpg)

A deliverista rides through Midtown with a DoorDash bag, Sept. 12, 2022. | Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

While all of the major app-based food delivery companies — including UberEats and Grubhub — sometimes lock workers out of their accounts, often with little to no explanation, DoorDash is the only one that routinely withholds workers’ pay when they lock them out, WJP executive director Ligia Guallpa alleges.

For nearly two years, the organization quietly negotiated nonpayment problems directly with DoorDash, deploying its staffers and even some volunteers — fellow Deliveristas — to bargain directly with company representatives. WJP claims it helped recover more than $200,000 in nonpayments from DoorDash this way.

But in recent weeks, Guallpa said, DoorDash’s communication with the group “has been less and less to the point where it’s unresponsive” — prompting the formal complaint to the city’s enforcement agency.

“I think what we’re seeing once again is the willingness of multibillion dollar corporations to not comply with the law, and who are willing to pretty much do whatever is in their power so they don’t have to pay workers, or to pay as minimal as possible,” Guallpa said.

The company said that it always prefers to deal with worker’s deactivation and non-payment claims directly.

“When outside groups stand in the way of our established resolution processes for their own gain, it’s Dashers that end up losing the most,” Scheinholtz, the DoorDash spokesperson, said.

One DoorDash worker who submitted a complaint against the company is owed $3,500, about a month’s worth of take-home pay, according to WJP. The company is among those that sued the city last month in an attempt to stop a rule that is supposed to force app-based food delivery companies to pay their couriers $17.96 hourly.

Workers lose access to their accounts for a variety of reasons, including if the company flags the user for sharing their account with others, or if a worker is unable to provide a Social Security or ITIN number, or even after a single negative review. DoorDash also deactivates accounts if the worker submits fake banking documents or does not submit bank information at all. Human error — like an incorrectly spelled name — can delay resolution of nonpayment and deactivation claims for months.

All DoorDash workers must pass a criminal background check and confirm their identity in a two-step process: they must provide valid government ID and submit a selfie that matches the photo on their ID. Anyone who is on the National Sex Offender registry or who was charged or convicted of a violent crime is banned from the platform.

Some, like Felix, claim they do everything right — submit all their documents, confirm their bank accounts, accept every delivery and accrue stellar ratings — and still lose access to their DoorDash accounts and get cheated out of pay in the process.

For DoorDash workers, regaining access to their accounts, and their money, can be grueling and demoralizing.

Fidel Vázquez claims he is owed $525 in wages and was locked out of his account in May because, similarly to Felix, the company did not send him a follow-up verification email even after he submitted all of his paperwork, he told THE CITY.

Tomás Ordóñez was unable to provide the company with a tax identification number and was locked out of his account in April after “dashing” for two and a half years; he claims the company owes him $1,400.

Freddy Toscano regained access to his DoorDash account after WJP intervened on his behalf — but he claims the company still owes him $500 he earned in the days immediately before he was locked out of his account.

And Rosendo Tacam was locked out of his account in April after receiving a negative review from a customer frustrated that Tacam, who was shopping for groceries, was unable to find the brand the customer wanted. Workers Justice Project claims DoorDash owes Tacam $450 in nonpayments.

All four workers have recently submitted complaints with the DCWP, and Tacam says they hope that many more in their situation follow.

“I think it’s important for us to formally submit our complaints,” Tacam said in Spanish. “These companies take advantage of us.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.