Nicholas Allen, Royal Holloway University of London

The United Kingdom’s next prime minister will be Liz Truss. After a two-month contest, Conservative Party members have chosen her as their new leader. All that remains is for Truss to travel to Balmoral in Scotland where she will be formally invited by the Queen to form a government.

Truss will become the Conservatives’ fourth leader and prime minister in just over six years. She’s Queen Elizabeth’s fifteenth prime minister, and the third woman to hold the job.

Her rapid rise to the top started in 2010 when she was first elected to Parliament. Four years later, she joined David Cameron’s cabinet as environment secretary. She went on to serve as justice secretary and then chief secretary to the Treasury under Theresa May, and as international trade secretary and foreign secretary under Johnson.

Truss is an avowed economic libertarian. She enthusiastically supported remain in the 2016 referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU but subsequently became a born-again leaver. She has preached the benefits of Brexit and adopted a notably hawkish stance against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine.

Truss’s brand of economic libertarianism, political optimism and hawkishness proved decisive in the 2022 leadership contest. Despite a number of gaffes and U-turns, her tax-cutting agenda, coupled with her erstwhile loyalty to Johnson, gave her a substantial edge over Sunak.

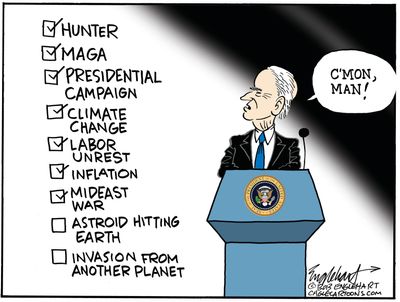

As the new prime minister, Truss faces a number of daunting challenges: rampant inflation, eye-watering energy costs, deteriorating public services, ongoing industrial action and an independence-minded government in Scotland. Overseas, she must contend with the war in Ukraine and troubled relations with the European Union.

Why did Boris Johnson resign?

Truss will replace Boris Johnson, who was compelled to step down as Conservative leader and prime minister in July. A mass resignation of around 60 ministers and other political appointees, including Sajid Javid, the health secretary, and Rishi Sunak, the chancellor of the exchequer, came in protest to Johnson’s mishandling of a scandal involving Chris Pincher, the government’s former deputy chief whip.

He resigned from that role after being accused of sexually assaulting two men at a private members club. Pincher said he had “drunk far too much” and embarrassed himself, but denied the accusations and remains an independent MP. Further historic allegations of sexual misconduct emerged, raising questions about what Johnson knew, and when.

Downing Street initially denied that Johnson had been aware of these allegations when appointing Pincher as deputy chief whip. This denial was later shown to be false. Johnson also faced criticism for not immediately suspending Pincher from the party, only doing so after coming under intense pressure from within his own ranks.

But Johnson’s hold on power was tenuous even before the Pincher affair. A string of scandals demonstrated his lax approach to standards in public life. A number of Conservatives had called on him to resign over partygate – revelations about boozy gatherings in Downing Street in defiance of COVID restrictions, which ultimately led to police fines for Johnson and his wife.

Johnson’s own conduct had became both distracting and cumulatively indefensible. No less than 41% of Conservative MPs voted against him in a no-confidence vote at the beginning of June.

Johnson’s perceived lack of direction was a second source of discontent. He could claim to have “got Brexit done”, but what was his government going to do next? There was much talk of “levelling up” but little of practical substance. The problems were compounded by the looming cost-of-living crisis and the apparent chaos of his Downing Street operation.

Lastly, Johnson had come to be seen as an electoral liability. The Conservatives had been behind Labour in the opinion polls since the end of 2019, and more recently had lost a string of byelections to Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Conservative MPs, especially in marginal seats, were worried.

The Pincher affair proved fatal for Johnson because it tapped directly into these sources of discontent. Johnson’s supporters claimed he was stabbed in the back by his own party – but after repeated stumbles, he had simply tripped onto his own sword.

RECOMMENDED READING