by Paul Bibeau, Virginia Mercury

May 2, 2023

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on the lynching of Noah Cherry, whose violent death at the hands of an enraged mob refuted Virginia’s carefully curated image as a moderate and genteel commonwealth. Part 2, which looks at the ways Virginia newspapers powered political disenfranchisement and brutalization of Black people, will be published tomorrow, May 3.

According to a news story, Medora Alice Powell was singing a Christian hymn, “The Sweet By-and-By,” as the 10-year-old girl left for school early in the morning on Friday the 13th of November in 1885. She took a solitary path through a portion of the rural area then known as Princess Anne County where Holland Road now snakes past a paint store, a tattoo shop and a Starbucks in southside Hampton Roads.

At the day’s end, following a violent thunderstorm, she didn’t return home.

A search party gathered and combed through the piney woods near the child’s home, retracing her steps. Late that night they came upon the scattered remains of her lunch before discovering Powell’s mutilated body in a gruesome crime scene within the dark scrub just a half-mile from her home.

When people found what had been done to Powell, it triggered deadly mob violence that escalated into the only publicly recorded lynching in what is now Virginia Beach.

Two Virginia newspapers, the Norfolk Virginian and the Richmond Dispatch, gave the first accounts of Powell’s death and were among the first to report the subsequent lynching of her alleged killer, a Black employee of the family named Noah Cherry.

The same weekend the Dispatch and Virginian’s accounts came out, Cherry was murdered by an angry crowd not far from the Princess Anne jail near the intersection of Princess Anne and North Landing roads.

The two deaths became a nationwide story, reported by newspapers from Maine to California. The account continues to surface in articles, in a book and on a true crime podcast. Alice Powell’s entry on the Findagrave.com database says, “This child was murdered by a young black man who had a grudge against her father.”

Reports of this case have made Noah Cherry the chief suspect in Powell’s murder for more than 135 years. They cast his lynching as an act of vigilante justice. But the reports of the timeline of when this crime occurred, and how authorities blamed Cherry for it, do not match a review by the Virginia Mercury of official records in the Library of Virginia in Richmond and files at the Virginia Beach Municipal Center.

All this comes to light at a time when Virginians are arguing over what to teach about the state’s history of systemic racism, as lawmakers in other states wonder if “hanging by a tree” could be added to official execution methods and amid shifting public sentiment about racism and racial history in America.

Lynching and its secrets

A 2017 report by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) shows more than 4,400 lynchings occurred between 1877 and 1950 nationwide. Virginia documented 84 of them within its borders.

The EJI makes a distinction between “frontier lynching” in the West and racial terror lynchings that occurred in the South. In frontier lynchings the subject was accused of a serious crime and given “some form of process and trial.” Southern lynchings were largely “extrajudicial” – without court proceedings – and racialized: The ratio of Black victims to white victims in Southern states was 4-to-1 from 1882 to 1889, increasing to more than 17-to-1 after 1900.

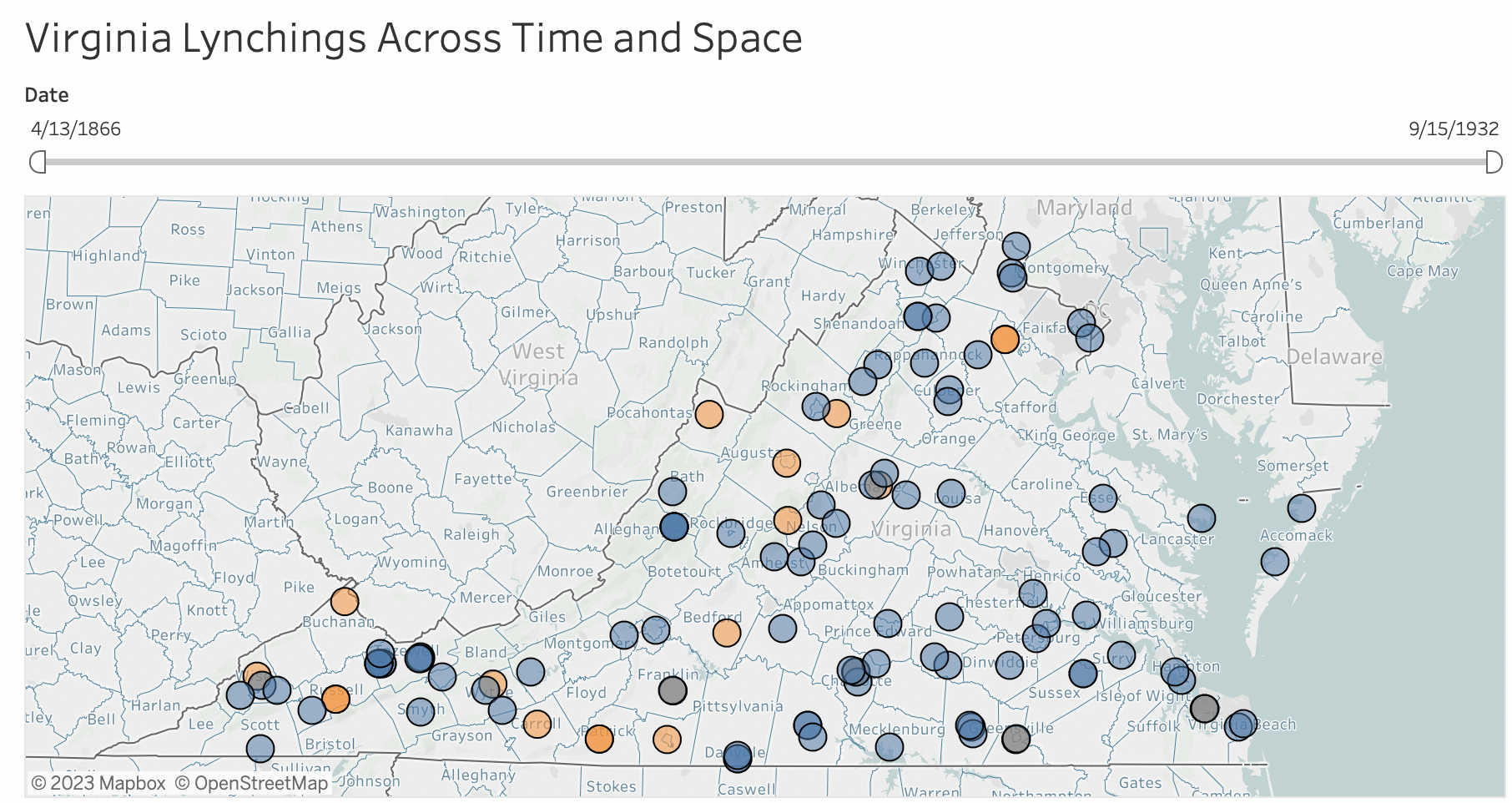

Lynching in Virginia was commonly triggered by allegations that Black people committed violence against white people, according to Gianluca De Fazio, an associate professor at James Madison University who directs a research project that has collected almost 600 historical news accounts of lynching across the state. This map, showing lynchings across the state from 1866 to 1932, is part of the “Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia” research project by Gianluca De Fazio, an associate professor at James Madison University. (James Madison University/ Gianluca De Fazio)

“It’s very helpful … to think of some kind of racial terrorism in which these lynchings are not just about punishing an alleged or perceived criminal,” De Fazio said, adding that the lynchings were often meant to send a message to the community not to violate laws or the racial hierarchy.

Cassandra Newby-Alexander, Endowed Professor of Virginia Black History and Culture at Norfolk State University, described how historically Virginia “managed the publicity” around racial violence to project a moderate, genteel image that wasn’t supported by facts.

“Virginia crafted a very specific narrative that they publicized internationally,” Newby-Alexander said. “They were keeping the more violent and extremist elements from impacting race relations and the state. But in fact the opposite was actually true.”

Two murders in 1885

According to the Norfolk Virginian, Alice Powell left her house near what is now the corner of Holland Road and Rosemont Road at 7:40 a.m. on Friday, Nov. 13, 1885. She walked west through a wild country landscape dotted with pine trees toward her school in Kempsville, then just a village of about 20 wooden houses.

The story said that when Alice didn’t come back after school, her parents assumed she’d taken shelter from a storm that had blown through the area that afternoon. But one of her brothers went looking for her and discovered she’d never made it to school.

“Alarm turned to fear,” according to the Virginian’s account. A crowd of people searched for the little girl and found her body about a half-mile away from her home. The Virginian’s description of her corpse was graphic:

“On the right side of her neck was a terrible gash, large enough to insert a man’s hand. … [H]er underclothing was torn, showing that the murderer had also attempted an outrage before the murder.”

The wound on her neck was allegedly so deep that when searchers picked up her body, Alice’s head nearly dropped off.

The Virginian said someone in the crowd remembered Noah Cherry had had an argument with one of Alice’s brothers and had sworn to get even. A constable arrested Cherry Saturday morning, and authorities gathered evidence against him through the weekend, finding Cherry’s blood-spotted clothing and Powell’s school books in a bundle near Cherry’s home.

The Virginian and the Dispatch both said a coroner’s inquest found Noah Cherry killed Alice Powell with an ax or hatchet.

After Alice Powell’s funeral that Sunday, newspapers reported that the clues found near Cherry’s house were “noised about the county,” and talk of lynching intensified. But both the Virginian and the Dispatch had already mentioned the possibility of lynching in their very first accounts of Powell’s death. The Virginian’s story came out before the funeral and publicized it as well as the possibility of a lynching.

A 2021 report by the University of Maryland’s Howard Center for Investigative Journalism found news accounts after Reconstruction often fueled racial hate and drove lynchings with their coverage.

According to an account from the Virginian, on Sunday night a crowd of masked people assembled near the jail. They marched to the jail at 11 p.m., forced the jailer to flee and seized Noah Cherry.

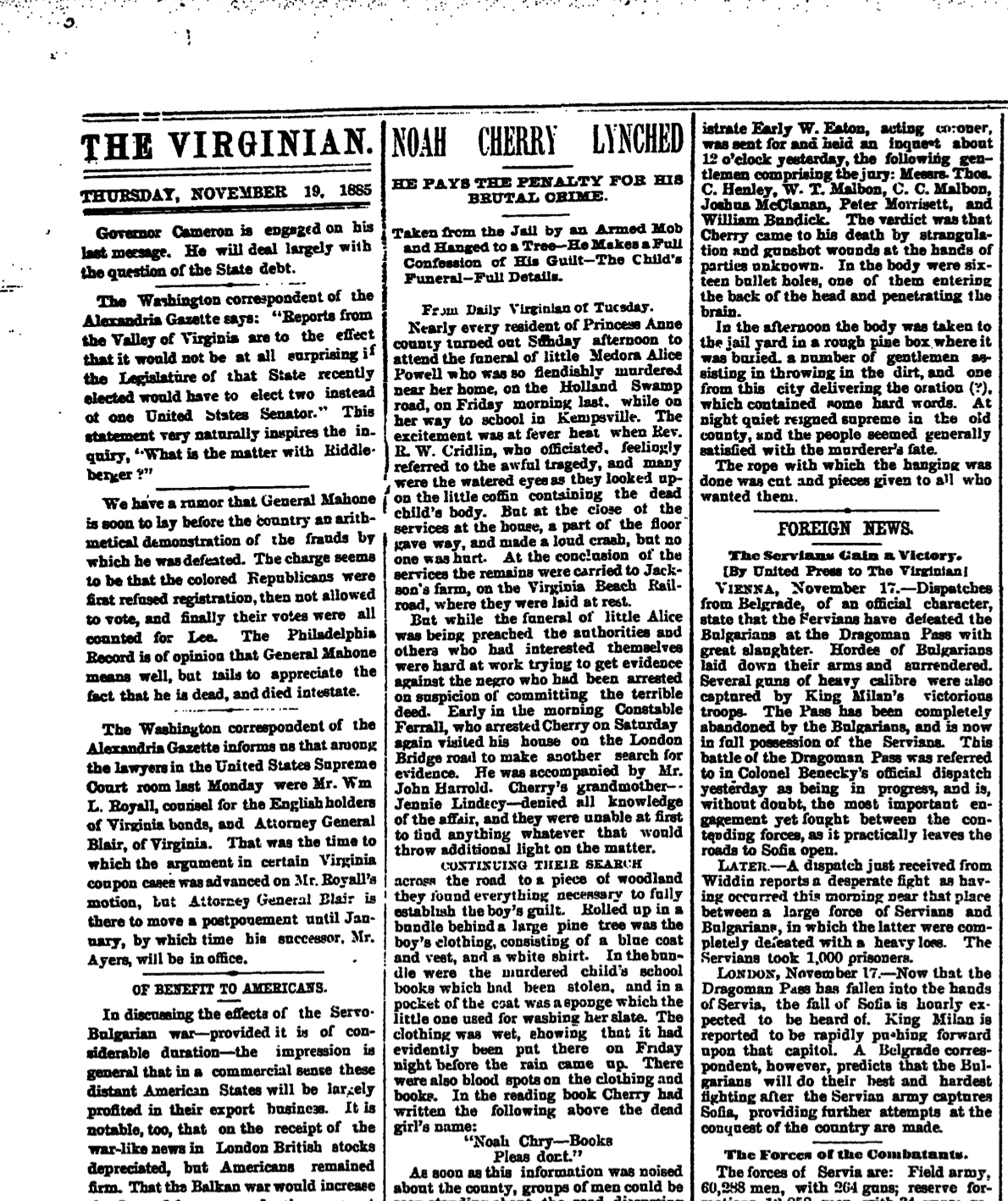

They marched him down the road to a nearby pine tree. According to the newspaper, moments before his death, surrounded by that angry mob, Cherry confessed to killing Alice Powell. The crowd then hung him and shot him more than a dozen times. The November 19, 1885 edition of The Virginian included an article about Noah Cherry’s lynching. (America’s News archive)

The day after the lynching, a Princess Anne County judge ordered Cherry’s body to be taken down, according to the Virginian, that said a second coroner’s inquest found that he’d been killed by unknown people. The Dispatch had fewer details, but also mentioned this second inquest. Cherry was buried near the Princess Anne jail, somewhere around the Virginia Beach Municipal Center.

What really happened?

The Virginian and the Dispatch published the first stories about Powell’s death in the Sunday, Nov. 15, 1885 editions of their papers. This was the day of her funeral and Noah Cherry’s lynching. Other Virginia publications followed with stories that Monday, and then coverage exploded across the country in hundreds of papers later in the week, according to a news archive search.

However, the Virginian and the Dispatch disagree with each other, and the county record, on the timeline of Alice Powell’s death.

The Dispatch said Alice Powell disappeared Thursday, Nov. 12 and was murdered that afternoon or evening. The Virginian reported she was murdered Friday morning, Nov. 13. The Virginian’s account is more precise, anchoring the timeline to a storm witnesses remembered. But the Virginian’s timeline doesn’t agree with Alice Powell’s gravestone, which says she was murdered Nov. 12.

What’s more, neither paper agrees with the Princess Anne death registry, a document in the archives of the Virginia Beach Municipal Center (and republished online), which says Alice Powell died Nov. 1. Her immediate family reported the death, according to the registry.

That registry said Alice Powell died more than 10 days before the story of her murder appeared in newspapers, just as authorities arrested Noah Cherry.

Furthermore, while the newspapers that led coverage of Alice Powell’s death and Noah Cherry’s lynching describe authorities gathering the evidence that made Cherry the suspect, there’s no indication in the court record that authorities did any of that. The two coroner’s inquests mentioned in news accounts – which were supposed to sift through evidence in the deaths – are not in the collection of coroner’s records for Princess Anne at the Library of Virginia. The Minute Book of Princess Anne County during the time period, which recorded jury proceedings and payments for jurors and coroners, also has no record of the investigations.

According to Newby-Alexander, it’s common for criminal charges against lynching victims to be thinly sourced.

“There is no ‘there’ there when you dig deeper into the story,” she said. “It’s almost as if all the racists in the nation got the same memo: ‘Blame Black men regardless of whether or not an actual crime existed. … You don’t even need to conduct a supposed investigation. All you need is the allegation.’”

SUPPORT NEWS YOU TRUST. DONATE

Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Sarah Vogelsong for questions: info@virginiamercury.com. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and Twitter.